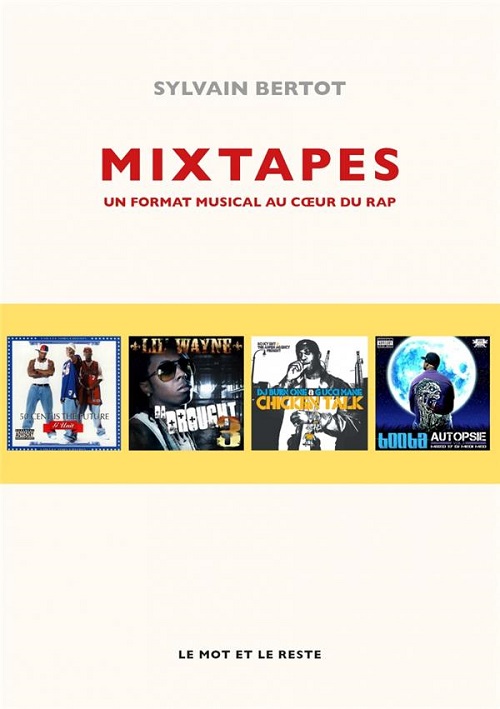

The history of rap cannot be told, without a strong focus on mixtapes. Originally compilations of existing songs, recorded and mixed by DJs on audiocassettes, they became over time real albums, distributed on the Internet, sometimes for free. A core component of the hip-hop culture since its very beginnings, they have been, sometimes, more impactful and of higher quality than official albums. After relating the surprising journey of the rap mixtape, through its multiple transformations, this book reviews a selection of 100 gems, released by well-established rappers like 50 Cent, Cam'Ron, Kanye West, Lil Wayne, or more recent ones like Future, Earl Sweatshirt, Danny Brown, Freddie Gibbs, Action Bronson, Young Thug or Migos.

The next few lines are translations of a few paragraphs from Mixtapes, a book written by Sylvain Bertot, in French only, about the history of the hip-hop mixtape.

Buy this book

Go to Facebook fanpage

Peace to Ron G, Brucey B, Kid Capri

Funkmaster Flex, Lovebug Starsky

Notorious B.I.G., "Juicy"

The mixtape was, originally, what its name means: a mix of existing songs, recorded on a tape. It was a byproduct of the audiocassette, a revolutionary format created by Philips in 1962, so popular in the 70's and 80's, that it would be a direct competitor to the major recording formats in these decades: first the vinyl record, and then the CD, or Compact Disc.

The first benefit of the audiocassette, was its flexibility. It was small enough, indeed, to be carried in a pocket, or in the glove box of a car. Thanks to it, and to the adequate equipment, music became more mobile. It could be heard in new places: in automobiles, or in the streets, after Sony created the Walkman, in 1979, or with huge boom boxes, with those ghetto blasters that would be iconic of hip-hop's beginnings.

The second strength of the cassette is that it allowed people to capture sounds, in addition to listening to them. Any individual, equipped with the right gear, could record whatever he or she wanted. With the advent of more sophisticated tools, like double table recorders, people could start transforming their rooms into small home studios.

Thanks to these, people could record pretty much anything. They could duplicate commercial records – the 90-minute cassettes was perfectly well designed for this, a full album could be copied on each side. But they could also immortalize their own creations. The potential of cassettes was high, despite a few limitations, like a painful hiss, and the ineluctable sound degradation after multiple copies.

Cassette Culture

Because it was handy, because it was easy to use it, or to send it by mail, and because it was cheap, the audiocassette became a favorite in multiple underground music scenes. Most notably, it was closely related to the emergence of independent labels, and to the do-it-yourself mindset of one of the key musical genres of these days: punk rock. While 60's / 70's psychedelic and progressive rock was the child of the vinyl album, punk music would be associated with a large cassette culture, celebrated by Sonic Youth's Thurston Moore in a book named after it.

By the late 70"s and early 80's, actually, in the post-punk UK and US, a few indie labels would specialize into cassettes. A few bands, also, would use them to release compilations, live recordings, promotional tracks, or even regular albums, predating what rappers would do with mixtapes, decades later. This phenomenon got so large, that influential music magazines, like the UK's NME, would dedicate full columns to reviewing cassettes.

In addition to their handiness, cassettes fitted perfectly well the radical and anti-establishment posture frequently associated with punk music. While some were worried by the potential impact of cassettes on the profitability of music - the same concerns would happen again, in the Internet era – its advocates considered, on the opposite, that this was a fantastic way to broadcast new creations. Such was the case with the Dead Kennedys. With their notoriously sarcastic mind, these Californian punk rockers would mock, in 1981, a famous anti-cassette campaign launched by the UK music industry. While its slogan said "home taping is killing music", the Dead Kens would write, on the cassette version of their In God We Trust, Inc. EP: "home taping is killing record industry profits! We left this side blank so you can help."

Punk rock's great contribution to music, is about democratization. It helped disinhibiting amateur musicians, even those who couldn't sing, even those who weren't guitar virtuosos. It taught them that they had a right to participate to the great rock 'n' roll circus. And the cassette played a part in this. But it liberated much more than just the punk rockers. Across the 80's, audiocassettes accelerated the development of multiple underground subgenres, like metal, hardcore, or others, all too extreme, provocative or radical to benefit from any support from the press, the radio or the television.

More generally, all the children or teenagers in the 80's have experimented its unlimited potential. Many of them massively bought blank tapes to copy at minor cost the records of their friends, or to capture their own music. And even more listened to their favorite radio programs, to catch at exactly the right time their preferred songs, and to create their personal compilations, their own mixtapes.

After its creation and commercialization in the 60's and 70's, the audiocassette reached its heydays in the 80's, a golden age related in a smart way in Nick Hornby's classic High Fidelity novel. This timing corresponded as well – and it is no coincidence – to the emergence of the mix culture, a new art of mixing and recycling existing songs, simultaneously developed in various genres like reggae and dub, disco, later on house, techno and rave music, and also rap. Largely funded on a do-it-yourself stance, the hip-hop culture was, actually, perfectly positioned to appropriate the cassette format.

Party Tapes, Battle Tapes, Radio Tapes

Born by the middle of the 70's, in New-York's impoverished African-American or Latino neighborhoods, the hip-hop culture was made of various disciplines: acrobatic dances executed on the ground (breakdance), more or less sophisticated scribbles painted with spray cans, on trains or city walls (graff), outdoor parties animated by Disc-Jockeys (DJs) experimenting new means to use their turntables (deejaying), and by Masters of Ceremonies (MCs) rhyming to the crowd in a rhythmic way (emceeing, or rap).

These disciplines, hip-hop traditionalists would later name the four elements, were not necessarily as intertwined as presented. This amalgamation was, for a large part, an ideological construction, a nice story, aimed at exalting a new culture born from poverty. They had all something in common, however: they were, essentially, and originally, executed by people with limited artistic legitimacy, or no access to high culture, who used anything at their disposal – mostly cheap, or stolen, or illegal, material – to express themselves, to become someone. They followed the same vulgarization dynamic as the one making creators or influencers out of cassette addicts. It is not a surprise, then, if hip-hop and cassettes had a long story in common.

The musical side of the hip-hop culture, later called "rap", would become a genre of its own, over time, exactly like jazz, rock, or reggae. But originally, this specificity was not granted. The hip-hop pioneers themselves, did not always understand that they created a new kind of music. It took visionary outsiders, like the rhythm 'n' blues singer and label owner Sylvia Robinson, to show that rap records could sell well, like with the single "Rapper's Delight". Previously, hip-hop was only about playing the records of others, with the help of a few technical tricks and the support of a rapper, in illegal outdoor celebrations called block parties.

The first key players of hip-hop didn't care much about creating their own work. Some knew, however, that their fans would enjoy listening to their music out of the block party context. As a result, as soon as in the mid-seventies, those willing to listen to the sound of the ghetto could do it on cassettes, either with the consent of the party organizers, or not, through bootlegs. Realizing that such cassettes could be highly profitable, some DJs decided to record their own. These, called "party tapes", would be rap's first media, even before it existed on commercial records.

According to Grandmaster Flash, he, Kool Herc and Afrika Bambaataa – three DJs acknowledged by the tradition as the originators of hip-hop – started recording mixtapes as soon as in 1973, the year the first block parties happened in New-York. DJ Hollywood, another pioneer of rap – sometimes discarded by hip-hop's mythologists, because he worked in the established world of nightclubbing, and not in the streets – claimed that, as far as he was concerned, he had started selling cassettes at groceries and barbershops as soon as in 1972.

Mixtapes, actually, were from day one a component of the hip-hop culture. And they were highly successful. Soon, a complete economy was created around them. According to Grandmaster Flash, his own mixtapes, sold to the likes of taxi drivers or drug dealers, allowed him to earn around 2,000 $ every month, which was quite a significant amount by these days. And to make these even more expensive and profitable, some DJs customized their mixtapes, providing their clients with unique selections fitting their own tastes.

…. next paragraphs, to be read in Mixtapes, the book.

THE DIPLOMATS - Diplomats Volume 1 (2002)

It was to promote his first single for Roc-A-Fella, that Cameron Giles released Diplomats Volume 1. Since his S.D.E. (Sports, Drugs & Entertainment) album, in 2000, and his arrival on Jay-Z's label, he was on his way to success. However, broadcasting his newest track on the radio, had not been easy; the subject matter of "Oh Boy", indeed, was the commerce of heroine... To overcome this ban, the rapper better known as Cam'Ron decided to go the mixtape way. And since his two pals, Juelz Santana and Jim Jones, contributed significantly to this release, he released it under the name of his crew, the Diplomats. A few other big names from Roc-A-Fella also participated to it, like Beanie Sigel and Memphis Bleek, but essentially, Diplomats Volume 1 was Cam'Ron's own project. Many tracks were his, and several would be included to his next album, Come Home With Me. This mixtape, actually, was a purer and rawer version of this record, minus its R&B embellishments. It was still an eclectic compilation, though, more than a well-thought work, with its succession of solo songs and freestyles, its introduction full of samples, and its rants declaimed on music from other people, like Carlos Santana's guitar on "Maria, Maria", or a revised version of Eminem's "Stan". Cam'ron only rapped on the latter, which was a perfect demonstration of his style. The Harlem rapper had amazingly harsh, cruel and funny lyrics on this dis track, aimed at his former friend Stan Spit. He destroyed his rival, literally, with no limit, going as far as ironizing on the death of his mother. And though, he also had the same sweetness as Eminem's in the original song, a gentle address to a suicidal fan. His flow would have its typical slow, smooth and easy tone, the one Cam'Ron owes his success to, which contrasts so well with his extreme and misogynistic stances, and fits with his bombastic beats. His beats, indeed, were fat and loud, as with the rock-infused "Dial Me 4 Murder", or this tour in the 'hood that was "Come Home With Me", featuring Juelz Santana and Jim Jones. But it couldn't go differently with Cam'Ron and Dipset, the ultimate ambassadors of a brazen and glittering ghetto rap style.

Other remarkable works: Diplomats Volume 2 (2002), Diplomats Volume 3 (2002), Diplomatic Immunity (2003), Diplomats Volume 4 (2003), Diplomats Volume 5 (2005), Cam'ron - The Purple Mixtape (2004), Cam'ron - Public Enemy #1 (2007), DJ Drama & Cam'ron - Boss of all Bosses 2 (2010)

…. other reviews, to be read in Mixtapes, the book.