Joe DelCarpini, a.k.a. Joe Beats, is a beatmaker from Rhode Island. He used to be the other half of Sage Francis' Non-Prophets, and pursued a solo career in parallel. Later on, he became part of another duo, with Blak from One Drop, before leaving the rap game. As part of our "Indie Rap Series", he is sharing his view about the underground rap scene of the late 90's / early 00's, through a full article of his own, pointing out the limits and side effects of the "indie" label.

The "indie rap series" is a cycle of interviews with key players of the late 90's / early 2000's independent rap scene in Northern America and beyond. Some of them are almost famous, some others are forgotten. These interviews will help building a book to be published in 2014, Rap Indépendant.

What is your perception of the indie rap scene that emerged in North America by the end of the 90's, with labels like Fondle'em, Rawkus, Stones Throw, Rhymesayers, or then Def Jux, Anticon, and so many others?

There were always artists independently releasing material - especially in and around New York. In fact, every artist can say they were independent at some point in their career; usually the beginning. But when I speak of "indie" I refer to more of a concerted effort to really take matters into your own hands to further one's career. A perfect example of this is Wu-Tang Clan. They were one of the very few to really make it from selling out of their trunk and into rap history.

From 1996 on independent efforts became more relevant because many respected rappers began making music for larger markets. By the time Nas released It Was Written as a follow up to one of the greatest hip hop albums of all time, things took a cynical turn. Not to say Nas' second record was bad. Although few will admit this, his writing actually improved from Illmatic. However, the production and packaging told the real story.

A good example is the video for "Street Dreams". The piece mimics the film Casino by Martin Scorcese. That was it: Nas conformed to the latest mafioso phase of rap in pop culture. I had no problem with the Lauren Hill collab. I loved the fact he teamed up with AZ. I thought it was great he worked with Dr. Dre. As spoiled as it sounds, including Foxy Brown greatly tainted all of the former associations.

Understand Nas brought hip-hop credibility back to New York. Sure Biggie was king but everyone knew he and Puffy were headed for the pop charts. Nas was not only the best lyricist but had a wise, poetic soul. No other rapper in the game - popular or not - had Nas' ability to be philosophical and serious but also uncorny. And then, in and around 1997, Nas caved.

That's not to say I wanted any of the above listed to be poor extremists with short lived careers, quite the contrary. It was just the way Nas made the plunge. He bent so easily to the landscape it seemed sacrilegious. Champagne? Armani Suits? Cuban cigars? Really man? All of a sudden everyone in the game was a really watered down, high fashion version of Kool G. Rap, minus the toughness and lisp. And now Nas, the man who made Illmatic, was too?

Preceding all of this, G. Rap and Rakim made really dope references to the Italian mob. But the latest incarnation of it during late 90's was nothing more than a New York runway show starring hip-hop gods. Now Nas was down with all of it? Wow. (Sidenote: I sincerely hope its bleeding through how big of a deal Nas' "turn" was.)

Contrast all of this with what another popular rapper from the early 90's was also doing at the same time: MF Doom. I heard "Dead Bent" around the same time I saw "Street Dreams". Why was the former work so much more appealing? It made sense. The transition from Zev Luv X to MF Doom was just as extreme as the switch from Nasty Nas to Nastradamus.

Zev went from selling bean pies in videos to mumbling, as if drunk while making noticeably lo-fi recordings. It was more pertinent not only did his brother SubRoc die but KMD were also dropped from Elektra right before their second album, Black Bastards was supposed to drop. And then the kicker: the record was canned because of the album cover, a depiction of little Sambo hanging from a noose (a whole other book for you, I presume).

Context is important. Doom arose from the ashes of KMD. Nas simply didn't want to get dropped like the aforementioned trio, Large Professor, or INI. Suddenly there was a noticeable void in hip-hop. Fans weren't entirely split in half but a good portion of disappointed supporters flocked to find what was lost.

Fondle 'em was the perfect refuge for fans because nothing represented true hip-hop music like Bobbito's radio show on KCR. The label was a natural extension to what the radio show did every week. Much like introducing the world to Black Moon in 1992, the Barber now put out the Clear Blue Skies EP by Juggaknots. The difference was independent releases had more of a chance of getting picked up in the first half of the 90's than later.

Again, a lot of artists put out their own material on wax in hopes of getting a deal. But from 1996 on (maybe as early as 1995), it was clear these records would solely be "indies". Their authors had no shot with majors unless they were willing to make some serious compromises. The frustrating part for groups like the Juggaknots was, had it been 1993 or 1994, they'd certainly be on Rap City, The Box, and MTVRaps. The strength of their subject matter might've turned some interest away but they'd definitely be better known than they are now.

To the aficionado, the high level of quality on tracks like "Clear Blue Skies" or "I'm Gonna Kill You" is so obvious. Unfortunately label execs were now expanding hip hop's market and placing their bets on non-enthusiasts. Looking back on it now, I assume higher-ups got sick of putting out one-trackers like Double X Posse, Rough House Survivors, and Zhigge. They wanted a higher return on their investment and the industry completed changed.

This is the point where the independent movement gained such a wide identity. It then encompassed everyone, from groups like Company Flow in New York to Dynospectrum or Atmosphere in the Midwest to the Living Legends on the West Coast. You think an aspiring artist in New York had it hard simply because they couldn't get picked up by a major? Try being from California or Minneapolis. That's what made Slug's ascent so amazing.

Luckily for all these artists, the Internet played a large role in the attention their music received. Pretty soon, college radio, record stores - online and off -, magazines, and webpages began clumping all of this "underground" work together as one big genre. It wasn't called independent or any shorthand. Underground was the effective label. It meant non-mainstream or, in other words, below the surface.

I'm not sure everyone came into the "genre" with the same intentions, definitions, and fervor but - like it or not - they had to live with the label. By that point the "scene" was ready made. In short, there were consistently clashes amongst many different types of artists who were "leftover" like everyone else. You might hear a mixshow play Buck 65's "Centaur" but then go into Casual's "I Gots To Get Down". Or worse yet, witness a rap battle between similar extremes. It was hilarious at first but quickly became the horrifying norm.

There was petty infighting because some artists didn't like being clumped under the same umbrella with others. Some rappers became so brave they began to reject the cult-like following of underground hip-hop. Out of nowhere mainstream rap for them was the shit - as if to paint themselves as more "cultured". The subtle implied was to reduce the underground scene to a bunch of groupie white males, upset black artists no longer catered to their tastes. Ironically these actions spoke to an even larger guilt and subsequent need to misappropriate.

Sadly these false notions touched on the future of undergound hip-hop. Certain faces garnered more attention from elements of the "indie rock" scene. For example, Def Jux was huge on outlets like Pitchfork. Slug (under the name Atmosphere) began touring the indie rock circuit throughout the US. And so on. Unfortunately a lot of dope artists were left out of this wave. Frankly speaking, most of them were non-white. Once again a group like Juggaknots remained independent while a majority of white artists got deals with punk, avant garde, downtempo, and rock labels.

My former group, Non-Prophets, fell into the latter group and was picked up by Lex Records -a subsidiary of Warp Records. We started out on an independent label out of our home state of Rhode Island called Emerge. Emerge was run by Emigrim Redzepi. He hosted one of the biggest mixshows in all of New England on WRIU 90.3. Mig held down the Friday slot from 3 to 6 pm every week. The show highlighted mostly independent releases.

Mig was friend with DJ Eclipse, also originally from Rhode Island. Eclipse managed the Fat Beats record store in Manhattan. He also backed up Non-Phixion, had his own mixshow, and occasionally guested on Stretch & Bob. Mig would hit the city, meet up with Eclipse, and come back with the latest independent releases. Mig eventually moved to New York, worked at the Fat Beats store and later as a liaison for their distribution company.

Mig promoted our two singles to names like Bobbito and many others. I remember going to the Bobbito show with Sage, Mig, and DJ Signify. I was under the impression Bob invited us. When we got there I was surprised to see Eclipse behind the tables and Lord Sear behind the boards. Sear clowned us. He implored Sage to wear a turtle neck when he rapped because of the veins created from straining. He called DJ Signify the cross eyed Dan Ackroyd. This was all opened up by Mig attempting to match with him in good fun. Sear called him a tennis ball boy: "you know the one that waits by the net for shots that go out of bounds". Bullseye.

Sage knew of the show but didn't know it through and through like Sig and I did. For example, I didn't say much because I knew how hard they snapped on unknown acts, especially those from out of town that probably weren't up on their inside jokes. Sear asked me why I was so quiet. Sage butted in, "he speaks with his hands." That one got an extended, "aaaayyyooooo....". I told Sear I knew what that meant and he laid off. Eclipse played "Drop Bass" and then went into a dat of "Follow Instructions" by MOP. It was weird but striking revelation: we didn't fit in.

Later that same weekend, we heard IG Off freestyling on Eclipse's show. They opened the phone line so callers could request whatever topic they wanted him to flow about. He'd rap 8 bars and then a caller would demand "yo, rap about going to the barber shop". Then IG would do 8 bars on that and then the next caller, etc. My perception back then was probably skewed but I rendered it so live and professional, New York was the major leagues of the underground game.

Up to that point Sage couldn't freestyle like IG yet. Back then, off the dome rapping was more of a pre-requisite for emcees than ever. In and around the same time, things like Lyricist Lounge were big in the city. More contrast to Non-Prophets. Even listening to my friend J-Zone - an oddball of the city - I couldn't shake the feeling we'd never make it by going through New York. Every beat sounded like a bad DJ Premier imitation. Jay was more boom bap than I was and had his own struggles breaking in. We spoke about it often.

I made beats with loops and breaks. My influences were Pete Rock, Large Professor, The Beatnuts, The Beatminerz, K-def, and so forth. I put my beats together on a computer, not a drum machine or keyboard. Thus, triggering chopped up sounds and placing a cheesy, short noted bass line in the open space wasn't my thing. I preferred a "this with that" style. Los Angeles Negros, "Tanto Adios" over Jeremy Steig's "Goosebumps". Create a filter sequence for the verse, bring everything in for the chorus, and we're good.

To most people in New York my stuff sounded 6 or 7 years too late. Even if it found the right place in time, it still would've been considered not "raw" or "street" enough. I like deep grooves and melodies. I worked within the break and never used kits to build drums. I wanted my beats to sound like a band playing. They might be out of tune for tempo's sake but will always be mixed in key... with few exceptions.

I was so frustrated back then at all these supposed beast producers getting over on the same cheap style. Making a beat by pushing a few buttons isn't very difficult compared to balancing four different 2 to 4 bar loops, all from different sources, and keeping everything in key. The level of difficulty was much higher working with bigger chunks of samples. I did that time and again on an old school program called SAWPro. Meaning, there's no pitch shift or time stretching in SAWPro like Acid.

Overall Non-Prophets were an odd shape attempting to fit into the neat circle of the New York City Underground. We began associating with other independent acts in other cities. For example, Akrobatik, Mr. Lif, 7L & Esoteric from Boston. We got along with most of those guys but still stuck out like sore thumb. Sage would later meet Slug and the Molemen while performing in Chicago.

In and around the same time Sage also began linking up with members of Anticon and even they dogged us a little. Our music sounded too traditional for them. After a certain point I wanted no part of Anticon; it was too far left. Sage and Sole hit it off quite splendidly. I remember Sole telling me, "Sage and I are cut from the same cloth". I didn't hate them. I actually enjoyed some of their music, mostly for the production. In fact, Moodswing 9 had a big impact on my style of making beats. He taught me a lot.

At the same time I learned an equal amount from a local cat named Aftamath. Math used only a 4-track and SP-12, the earlier version of the SP-1200 with less sample time. Math was from the deep hood of Providence. His music greatly reflected that, manifesting as an extremely hazy (almost psychedelic) version of Raga rap; more dark and blunted than Black Moon. He released a bunch of independent albums under the label name New Realm. My music became a blend of the two extremes: digging aspects of Moodswing mixed with Math's courage to let things be.

Why are these personal anecdotes noteworthy? To prove how different everyone was despite having a big label like "independent" and "underground" bestowed upon us. Anticon was "independent" but so wasn't New Realm. Rhymesayers was just as "underground" as Virtuoso. There's a mammoth abyss in between all of those names.

As an artist I couldn't help but lose sight of everyone without a major deal as the same thing, even though we were constantly grouped together. I blame the marketplace for needing a label but I also blame the novice "indie" consumer for falling for the romance of it all. A lot of kids were simply fans of counter culture or the underbelly of culture - particularly within art. They had little knowledge of the Juice Crew, let alone someone more obscure.

These fans adored the independent punk and rock movements just as much and probably had a front row seat for one or both. Now it seemed hip-hop's turn so they flocked. They might've caught on as early as 1997 or hopped on as late as 2002. Whatever the case, they moved on to the next interesting genre shortly after. Most likely something going on in Williamsburgh, Baltimore, Philly, or certain neighborhoods of Los Angeles.

Your persona had to be of cultural significance to stay afloat with that crowd. For example, Tay Zonday's "Chocolate Rain" held more cultural phenomenology than Joey Beats & Blak. If I ever thought the New York wall of the late 90's was tough to scale, breaking into the "indie" scene with groups like MGMT and Animal Collective was impossible.

The above Youtube sensation explains of why it's tougher distinguish when something is "indie" or not. Odd Future are a fantastic example of a group everyone was led to believe did everything on their own. That's an important lie of omission. They were helped by Christopher Clancy and another dude from Interscope. Don't get me wrong, Odd Future clearly deserved all the attention and fandom they got. But the campaign around them was specifically designed to appear as grass roots, down the street, in the basement, pure and untouched.

Big stars have official fan pages and Twitter accounts. Why does that matter? Because 15 years ago a top 40 artist would never press up their own vinyl in a small run hoping to further their name. Independently pressing your own work because you were at such a low level in the business was a necessity for an artist that wanted to further their career and had no other option.

Youtube, Soundcloud, and sites of the like became the new platform by which "indie" artists "released" material. The problem is this outlet wasn't exclusive to them. The comparison is not in the platform or medium; wax, tape, or CD. The comparison is the location and place of where such recordings could be found. Soundcloud is not Fat Beats or The Source Magazine. I'm sure boutique havens exist but, at this age, I have no idea where they are. And if they do exist are people with money really frequenting such places checking for new acts?

A couple might be Worldstar or Vice but I'm not so sure many acts make it big after being on there a few times. Again, I concede I might simply be out of touch in this regard. However it seems to me new artists require some sort of voucher from another well liked name or conglomerate to separate themselves from the pack. And I'm not talking simply about paying Drake to guest on your work. I'm talking about a name in the same ballpark as Drake pushing your work and riding for you like he did with the Weeknd.

The closest thing that resembles anything remotely near to the early days of the independent movement in hip-hop is probably the current rap battle scene. I state as much because there is some semblance of a community that revolves around specific events. Coincidentally a lot of these battlers make very boom bap, late 90's style music off stage and in the studio. It's clear they grew up on and were influenced by that era of hip-hop.

Their scene might seem vitriolic but it's based upon the ethic that simply being skilled in the trade and artform is the most important thing. The little man behind the curtain of all facets in the entertainment business laughs at such foundations. The harsh truth is being anti-ethical within the bounds of political correctness is what's rewarded most in the industry. I feel bad that a lot of people working hard to make it don't know that yet.

In the entertainment business talent doesn't mean the same thing as skill. Behind desks and in offices, "talent" is a euphemism for a level of narcissism. What's the return on my investment? Will this person talk about themselves and their work as if it's the most important thing in the world for the next 20 years without a drop of regret or shame? That's talent. A craft or skill can be learned that can be taught later. The upper echelons of ego and narcissism are touched by few.

As jaded as it might seem, this is how I now view the entertainment business. Why is that important? Because anything "indie" is merely a step on the ladder to a bigger place - as it always was. Many artists won't break the kayfabe of their persona and tell you they would turn down bigger opportunities for career expansion for "ethics" or personal "politics". I don't believe most of it.

The entertainment business (and yes, indie scenes are included within that) is a capitalist machine. There are wonderful moments of rebellion and great things temporarily arise to represent a space in time. But ultimately, everything gets swallowed up by the same system. Then another thing pops up somewhere else and the romantics give chase. It happens over and over. If people want to believe there is an independent scene or kind of independent music, let them. It's their right. It's their escape.

As for me, I haven't made a beat in three years. It wasn't a conscious choice; it happened because my adult life crept in and took over. I cleared up a lot of debt, returned to school, and got my bachelor's degree in English. I considered attending Law school but listened to 10 of the 12 attorneys I spoke to and decided against it. I'm currently looking for a better job.

I am about to purchase the Ableton Push :)

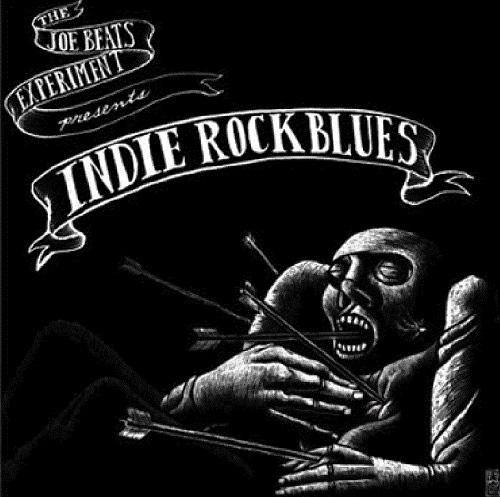

You are explaining how the underground rap scene evolved, from something centered on New-York, to less classic hip-hop aimed at indie rock fans. Some consider Indie Rock Blues, an indie rock songs remix album, one of your finest releases. Was this record your attempt to seduce indie rock fans, or something you really wanted to do? Or maybe a mix of the two?

About Indie Rock Blues... the project was genuinely something I wanted to do. I always tried to sample things that hadn't been touched. For example, in the late 90's/early 2000's all producers went crazy for Soundtracks and Library records. So I found latin music: Los Angeles Negros, HNos Castros, Chucho Avellant, etc. In fact, all of Non-Prophets Hope is basically latin loops. Then Latin music caught fire and so I moved on to Bossa Nova and Brazilian. Then Brazilian became all the rage and I got fed up.

I lived in an artist commune. I became very close with the guy across the hall from me. I admired Sonny's work (google CW Roelle) and always found myself hanging out in his studio. I played him black music and he played me indie rock. While listening I began finding drums and loop chunks to sample. It came at a perfect time because I was looking for new, untapped sample sources. I made a Non-Prophets remix using a loop from one of Will Oldham's live shows. It was never released because Sage and Lex really weren't into it - musically speaking. Shortly after we began prepping for tour.

After our tour completed, four months later, I made the remix for "Coxcomb Red". I played it for my friend Sonny and he encouraged me to keep on with it. I did a bunch of research myself but he just kept feeding me CDs of songs to potentially sample. After a while I found myself remixing the songs more than I was actually making emcee style beats from them. Some like "When We Reach The Hill" and "Panda, Panda, Panda" are straight ahead tracks, bare without a rapper. Others like "I", "Coxcomb Red", and "Save Yourself" are straight ahead remixes. The rest of the bunch sit somewhere in the middle of both extremes. The "tweeners" also happen to be my favorites: "Spaceboy Dream", "Doomsday"," Sad Song", and "Exploration vs. Solution".

I made all of Indie Rock Blues on SAWPro, a multitrack program from the mid 90's. In short, it was extremely difficult. If I could re-make the same record in less than a month using today's technology of Abelton, etc. I started IRB in the summer of 2004 and didn't finish until summer of 2005. Then it took 3 months to press and then another month of prep before putting it up for sale.

This is important because I feel if it were released a year earlier, it would've gotten a lot more attention. At the same time I'm not so sure it would've been the exact attention I wanted for the project. Everyone thought it was simply too desperate and forward to garner specifics types of indie fans. To this day, I get the same reaction from people who finally listened to it years later. At first they thought it was simply a "mash-up" of stuff and quickly discarded it.

At the time of its release I knew full well this would be a big obstacle for the project. It was very niche but at the same time how it would be presented meant almost everything to its success. I didn't want to come across as pandering to specific base nor did I want the album to be seen as a temporary gimmick. Thus, we promoted it to bloggers and small websites, hoping to catch on through word of mouth. It did and it didn't. In the end, I am very happy at the attention it received. Even if a classic hipster is proven wrong 10 years later, that's enough for me.

The only negative responses I get from these hardcore Jeff Magnum and Neutral Milk Hotel fans. These same people got all excited that Dangermouse wore a NMH shirt in a press shoot but are all up in arms over my remix. If that doesn't tell the full story, I don't know what ever could.

So, in the end, I felt the record came about very naturally. Upon completion I realized how badly it could be labeled and reduced. As a result, I was really frustrated because I just spent the whole year busting my balls on the most difficult, ambitious project I'd ever done. To make matters worse, that very emotion could be reduced to things EVERY artist goes through as their music is about to be marketed as a product. Shrug.

You are mentioning your discussions with J-Zone, and indeed, your views on hip-hop, or life in general, are quite similar to those he shared in his recent book, Root For The Villain. I assume you read it, what did you think of it?

My good friend gave me Zone's book as a gift. Although I still talk to Jay, I put off reading for a while. I didn't want to read something I was 1) going through and 2) just about to be over. Then one weekend I plopped myself down and finished it. Good decision. I laughed aloud many many times.

I love Zone. I have an odd, odd connection to the man. We go back about 15 years. Throughout, our paths have crossed many times and it's been all good. I don't think Zone knows this but my interactions with him or his art have always had an impact on my life.

He met and became cool with Mig when I first 12" came out. They helped each other's records as much as they could. I remember Mig giving us a bunch of Zone's stuff to play on RIU and to give away as promos to DJ's back home. I heard his music and immediately fell in love with it.

Years later, he actually teamed up with Dangermouse for his first single on Lex. Then we got signed to that label. During the Non-Prophets Hope release I shouted him out in as many interviews I could. Even his record release party at Serena Lounge was some shit for me personally. Weird.

I gave him the loop for the song he did with Breezy Brewin; "The Lemonade Joint". I still bump that shit from time to time, happy as hell I had even the smallest thing to do with it. He asked me about that joint for about 7 years before I let up on it - hahah. He is so good at producing; I can't even begin to explain. And dudes who make beats and know beats will tell you that.

Now there's his writing. From the minute he began blogging for Dante Ross, my life switched to being less music orientated; the real world hit. His posts up until the release of his book were with me every step of the way. He is one of the most honest people in this industry. Unfortunately for him and many others, truth is not as celebrated as it should be. Even, ironically enough, in the independent DIY scene where everyone is supposed to ordinary moes just trying to make genuine art.

Jay's courage bled through in his music and now torrents through in his writing. A lot of these guys on Twitter, Vine, Facebook, Instagram, and whatever else are fronting about "grinding", "doing big things", or "on the brink". Zone tells it how it is. There's no posturing. And I love him for it.