Published on May 2, 2025,

by Velocity Press.

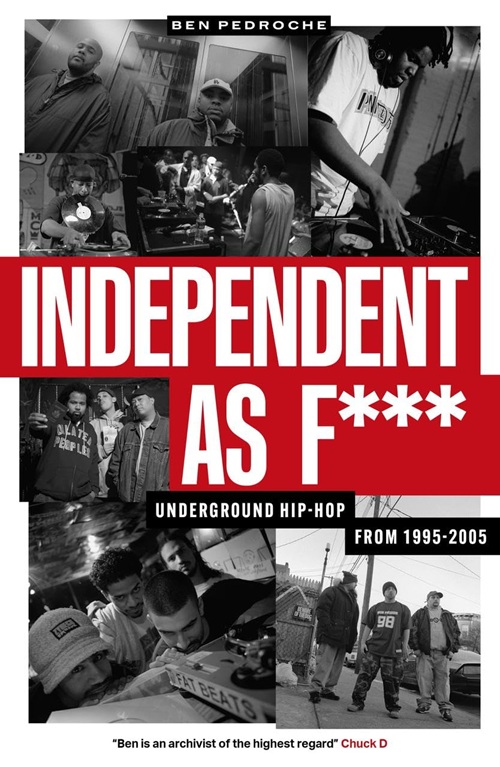

2025, a year of remembrance for independent rap. In recent months, no fewer than two books devoted to this thirty-year-old movement have been released. One of them, of course, is the reissue of Rap indépendant, la vague hip-hop indé des années 1990 / 2000 en 30 scènes et 100 albums. And since May, it has been accompanied by a brand-new work, Independent As F***: Underground Hip-Hop From 1995–2005, written by British author Ben Pedroche, his first book about music.

These two works are, in fact, the only books in the world dedicated to this moment in American rap. They're both written by Europeans, and that’s not illogical. From France and the UK, it has always been hard to grasp the latest evolutions in rap. American streets are far away; we’re not exposed to them. But indie hip-hop, on the other hand, was a critics’ darling. It was documented, and it crossed the Atlantic. As underground as it was, this movement was in reality well covered by specialist media.

In the ’90s, the highly influential British music press wrote about it, and the Internet quickly took over. It was mainly through these two channels that we discovered these scenes. Their audience was literate, nerdy, intellectual, and - let’s be honest - largely white. And still today, while it’s hard to find written information about street rappers who are far more popular, reviews are everywhere when it comes to the latest Aesop Rock release.

Yet this movement was much more than a media flash-in-the-pan. It was, in many ways, significant in the fascinating history of rap. It contributed to its diversification and regionalization. It embodied rappers taking control of their own destiny - a trend also illustrated by the Wu-Tang Clan, Southern labels No Limit and Cash Money, Jay-Z, and many others. It helped legitimize rap among audiences that were foreign to it. And it pioneered online promotion and distribution of music.

But what exactly are we talking about? Let’s set the stage for those who didn’t follow.

At the start of the ’90s, rap was entering one of the best phases of its history. Because it proved commercially lucrative, the industry invested heavily. It gave many rappers the means to achieve their ambitions. But in return, labels sought to optimize their artist rosters and business strategy. They imposed their views, made choices, and dropped artists they deemed unprofitable or who refused to follow their directives. Put off by this attitude, and remembering that hip-hop was originally carried by small labels, some artists took their fate into their own hands.

And so came Fondle’Em, Rhymesayers, Stones Throw, Def Jux, and all the others. Dozens of small structures emerged to support unknown, marginal, or label-rejected rappers. Many of them would disappear. A few, more rarely, would become institutions. Unlike other indie labels - especially Southern ones - whose sole goal was to become as big as the majors, these labels often adopted an ideological posture: reverence for hip-hop’s origins, priority of aesthetics over commerce, and distrust of the music industry (and sometimes of big capital in general).

Company Flow became the flagship group of this movement, the one that gave it its ideology and defined it with a slogan, the sharp and punchy “independent as fuck,” which gives Pedroche’s book its title. With them came a whole universe. In New York, but also across the U.S. and in neighboring Canada, hip-hop’s outsiders banded together into a vast underground network, united by their disdain for Puff Daddy-style rap and the genre’s commercial pivot.

Ben Pedroche is thus the second person to take us back to this period, and the first English speaker to paint a full panorama of it in rap’s “native” language. And he does so seriously.

Shorter than others, his book covers the essentials in several sections. He reviews the context in which this movement emerged, through a brief history of rap in those years. He introduces the key figures, scene by scene, label by label, just as Hip-Hop Indépendant did. He continues with a selection of albums and EPs, a list he is careful to describe as subjective, even if it’s fairly predictable. And he closes with a chapter on the legacy of this movement, and on those who keep the flame alive today.

It’s well done and quite rich - so much so that even when you’re very knowledgeable about this era and this movement, you can still learn things. (For the record, I didn’t know that American rapper Mr. Lif and Canadian rapper Eternia were husband and wife.)

Only two minor criticisms can be made about Independent As F***. The first is that it’s more of an encyclopedia than an essay, thesis, or argument. This book reads like a collection of entries, each describing or contextualizing a rapper, album, or label in a few words, with a flood of names that border on name-dropping (as with Rap indépendant). It’s a book to dip into. And why not? It’s a valid choice. A book can be read that way too.

The second limitation is common to other music-related books. Wanting to present a period that personally marked him, Pedroche reproduces it exactly as it was, without much hindsight, reinterpretation, or revisionism. Though the author is a specialist in London’s history, his approach is that of a fan rather than a historian, critic, or essayist. His book presents independent rap as the media described it at the time: the artists covered are those on the specialist press’s radar; the albums discussed are the ones being celebrated then. He condenses, compiles, and recounts, but adds relatively little in the way of new insight.

The focus stays mainly on the East Coast. We don’t explore every corner of the West Coast underground. There is no detailed dive into the multiple successors to Project Blowed. For example, although some of their members are mentioned, the ShapeShifters never come up. The book devotes a few pages to the important slice of the indie scene living in Canada, but doesn’t really go beyond Halifax, Toronto, and Vancouver. Chicago rappers are mentioned, but Galapagos4 is ignored. We’re told, unequivocally, that Movies For The Blind is Cage’s best album, without celebrating Hell’s Winter. The author claims that Aesop Rock’s serious work only began with Labor Days, and since the earlier material seems to him like mere warm-ups (and perhaps he didn’t know the rapper pre–Def Jux), he assumes Aesop had never featured other rappers before Float. (Wrong: Dose One was already on Appleseed.)

Independent As F*** does the job. But it’s a bit neutral, tame, predictable, and risk-averse. The underground movement was important; it absolutely deserves to be understood. This well-executed, solid work is therefore another indispensable entry in rap historiography. However (and sorry for the lack of modesty), it’s not the best book on the subject. It will forever be second.